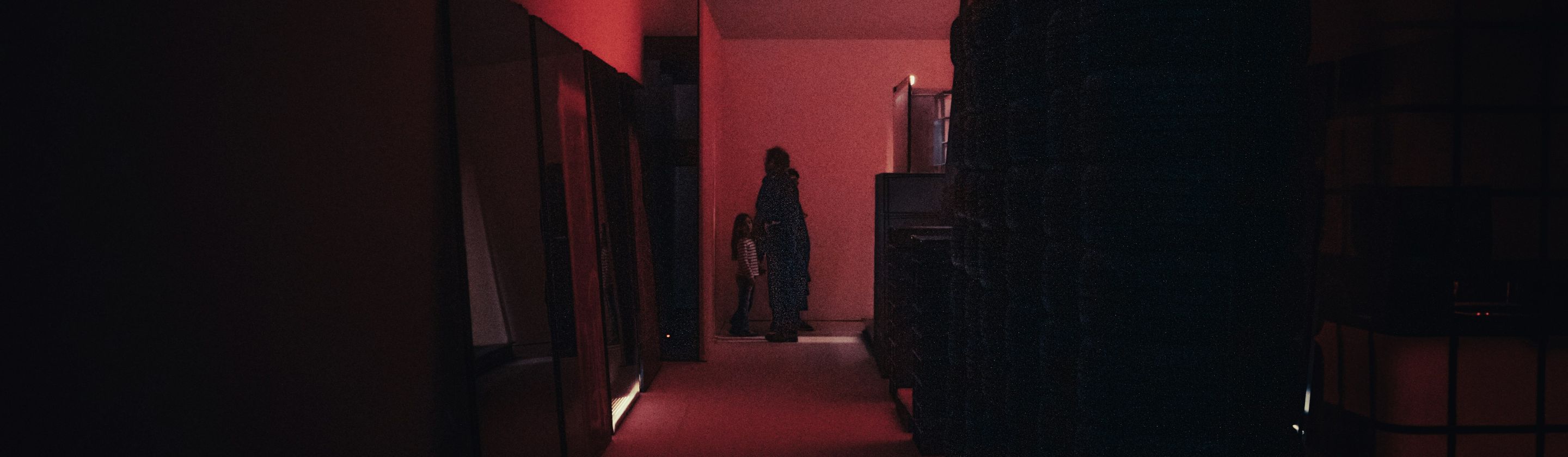

Evgeniy Kondratiev on Unsplash

Evgeniy Kondratiev on Unsplash

Every gamer knows the feeling. The boss has one sliver of health remaining. Victory seems inevitable. Then a poorly timed dodge, a missed parry, or a moment of overconfidence ends the attempt. The death screen appears. Most rational responses would involve frustration, maybe taking a break, perhaps lowering the difficulty. Instead, we immediately hit retry, eager to throw ourselves at the same challenge that just defeated us. This loop of death and retry defines some of gaming's most memorable experiences, yet the psychology driving players to voluntarily suffer through dozens of failures remains fascinatingly complex.

Boss fights occupy a unique space in game design. They serve as skill checks, narrative climaxes, and pacing mechanisms all at once. Unlike normal gameplay where players often succeed on first attempts, boss encounters expect failure. Developers design these moments knowing most players will die repeatedly before achieving victory. The question becomes why players accept and even embrace this masochistic bargain.

The Learning Loop That Hooks Us

Each boss attempt teaches something new. The first death might reveal a devastating attack pattern. The second shows the tell that precedes it. The third demonstrates the timing window for a successful counter. This incremental knowledge acquisition creates a powerful learning loop that keeps players engaged despite repeated failures. Research on skill acquisition shows that challenging tasks with clear feedback produce stronger motivation than either trivially easy or impossibly hard challenges.

Boss fights exploit this psychological sweet spot ruthlessly. FromSoftware games like Elden Ring and Dark Souls became famous for this exact formula. Fighting Ornstein and Smough in Dark Souls means learning which one to target first, how their attacks complement each other, and the precise timing to roll through Super Ornstein's charging spear thrust. Players might spend hours learning a single boss, dying fifty or more times before victory. Each death feels educational rather than purely punishing because the path to improvement remains visible. The boss has patterns and those patterns can be learned. Progress happens in understanding rather than character stats, making each attempt feel meaningful even when it ends in failure.

The retry speed matters enormously to this loop. Games that load quickly after death and place players immediately back into the fight maintain momentum. Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice allows players to resurrect instantly during boss fights, minimizing the gap between failure and the next attempt. This design choice keeps players in the flow state where frustration never has time to calcify into genuine anger. Learning to deflect Genichiro's lightning reversal or memorizing Isshin the Sword Saint's four-phase moveset becomes addictive rather than aggravating. The deaths become data points rather than setbacks.

Mastery and the Illusion of Control

Humans crave control over their environment and outcomes. Boss fights offer a particular flavor of control that normal gameplay cannot match. When players die to a boss, they can identify the mistake. The dodge came too early. The heal attempt happened at the wrong moment. The attack was too greedy. This attribution of failure to specific, correctable errors creates the illusion that perfect execution is achievable.

This differs fundamentally from random or arbitrary difficulty. A boss that kills players through unpredictable patterns or unfair mechanics generates frustration and abandonment. A well-designed boss creates a puzzle where skill provides the solution. Players believe that mastery is possible, that enough practice will lead to perfect execution. This belief persists even when the execution requirements far exceed what players can currently achieve.

The Cuphead experience exemplifies this dynamic perfectly. Defeating bosses like Grim Matchstick or King Dice requires precise timing, pattern memorization, and sustained concentration across multi-phase encounters where attack patterns shift completely. Players die constantly, yet the game maintains a devoted following because every death feels earned. The player made a mistake. The boss telegraphed the attack. Success requires only better execution. Similarly, beating Mike Tyson in Punch-Out!! demands memorizing his entire sequence of punches and uppercuts, recognizing the one-frame tells that signal each attack. This framework transforms repeated failure into a challenge to personal skill rather than a flaw in the game design.

The Narrative Weight of Earned Victory

Stories have more impact when protagonists struggle before succeeding. The same principle applies to interactive narratives. A boss defeated on the first attempt provides minimal satisfaction. A boss that required twenty attempts and two hours of concentrated effort becomes a personal legend. Players remember these victories with clarity and pride precisely because of the suffering involved in achieving them.

Gaming communities have built entire cultures around this shared experience of struggling against difficult bosses. Forums and social media overflow with tales of finally beating Malenia in Elden Ring after learning to dodge Waterfowl Dance, or conquering Sigrun in God of War by mastering the timing on her valhalla stomp. These stories resonate because they represent genuine achievement. The difficulty was not artificially inflated through random elements or unfair advantages. The boss had learnable patterns. Victory required skill, persistence, and mental fortitude.

Boss fights work because they transform failure into fuel. Each death teaches, each retry builds skill, and each victory earns genuine pride. We keep dying on purpose because the alternative, succeeding without struggle, would feel hollow. The difficulty is not the obstacle to enjoyment. The difficulty is the point.