In its decades-long quest to mimic life, robotics has never had much trouble duplicating its brute force. Machines have long been capable of moving vehicles, assembling chips, and reaching the far corners of the solar system. They have faltered at replicating the exquisite delicacy of even the smallest creatures in nature. This is rapidly changing. On the boundary between robotics, biology, and engineering, MIT researchers have created insect-scale flying robots that are not only capable of sustained flight, but also begin to look, and act, more like true flying organisms than machines. They move through the air in ways that are at once lighter on the power budget and more tightly woven with the guiding principles of living systems: principles that are the product of evolution, not brute-force engineering.

The potential implications of this are as broad as they are tantalizing. A future in which the most pressing concerns of agriculture, climate, and food security are answered by robotics that are less like machines and more like life may be closer than it sounds.

Robotic Pollination

Artificial pollination may be one of the most far-reaching applications of MIT’s robotic insect research. As real-world pollinator numbers have come under increasing pressure from habitat destruction, pesticides, and global climate change, many have looked to lab-based approaches as a possible large-scale alternative. Deployed en masse, robotic pollinators would let humans farm crops indoors, in multi-story warehouse farms, with vastly higher yields and lower land area, water use, and environmental impact.

Insect-size robots have existed for some time, but their capabilities pale in comparison to a real honeybee. Biological pollinators are feats of endurance, efficiency, and precision, qualities that most microscale machines have struggled to match. Not anymore.

MIT’s new robot reimagines the design of the insect around the biological form and flight dynamics of real pollinators. The resulting robot, with a mass of less than one gram, can hover for about 1,000 seconds. That’s more than a hundred times longer than previous iterations. The robots also fly at faster speeds and can execute complex movements, including flips midair, while the motors last much longer between mechanical failures.

Lightening the mechanical burden on the artificial wing joints, while making every motion as precise as possible, can help with all of the above: longer flight time, tighter control, and much longer-lasting hardware. There’s also room inside the chassis for miniature batteries or sensors in future work. That could eventually mean untethered flight in real-world settings, instead of just the lab.

A Problem in the Making

Insects was that they didn’t quite resemble the lifeforms they were modeled on. Earlier versions, for example, were constructed from four identical modules, each with two wings of its own, which produced a blocky eight-winged contraption with none of the sleek, geometric simplicity of any natural insect. Each individual module flew just fine when tested in isolation, but when all four are assembled into a single machine, it has trouble getting enough lift, much less going fast or efficiently. Having too many wings also messes up the airflow, pushing more air downward than necessary and producing less lift than one might expect.

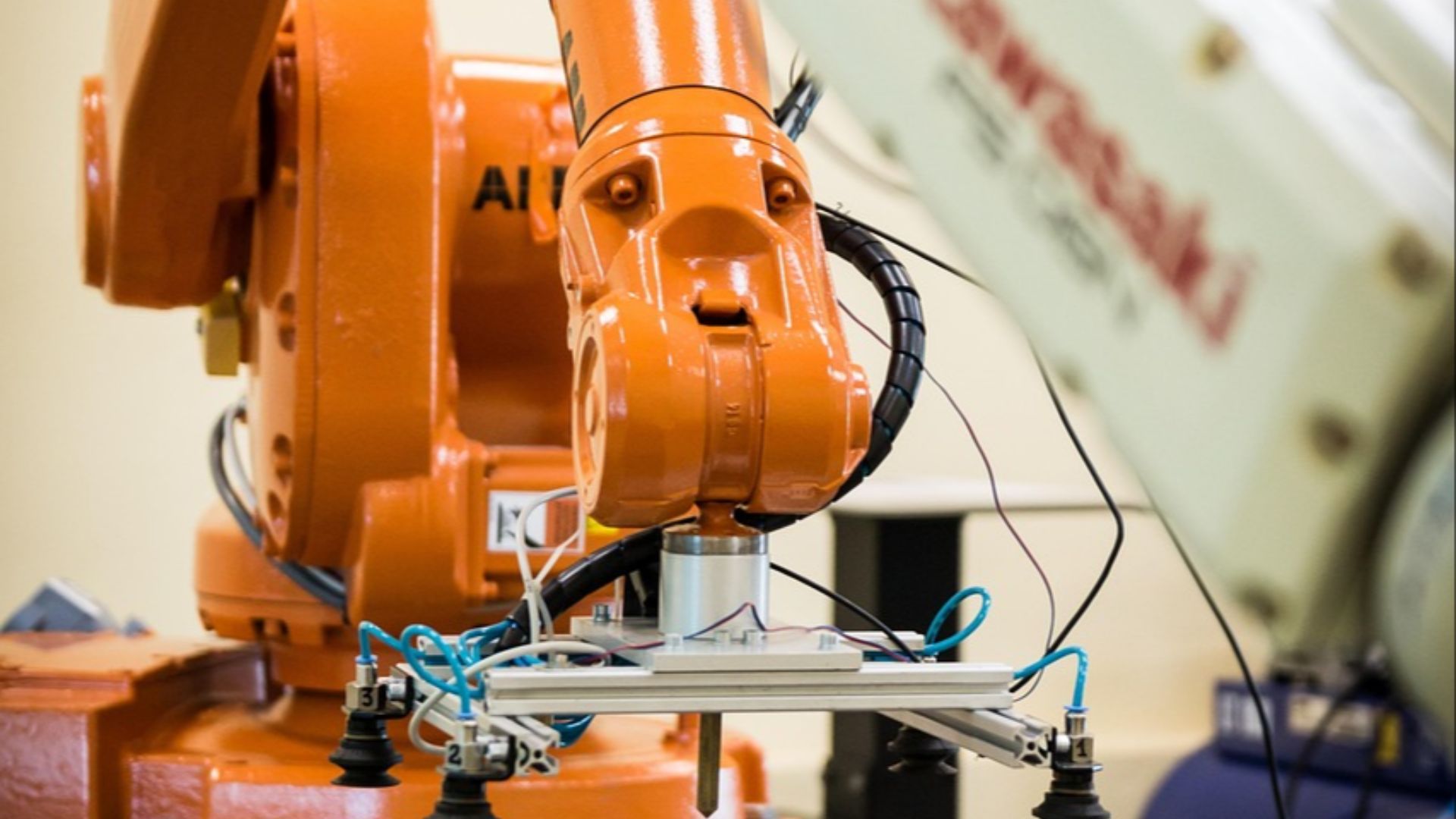

The way MIT got around this was to literally take the robot in half. Each module in this new design has only one wing that flaps outward from a central point, which keeps the robot more steady as it moves up and down. The simpler design also has the added bonus of freeing up space for electronics inside the robot, which will be needed if it’s ever going to become fully autonomous.