The Internet is a far different place than it used to be 20, 10, even 5 years ago. For starters, sites like Webkinz, Neopets, and Club Penguin are either defunct or shadows of their former selves. While the Internet used to have colorful spaces for kids to build community, now it's filled with graveyards flash games littered with ads.

What Happened To Club Penguin?

The Internet connects more people today than ever before, yet it's become less of a community than it used to be. While this focus on algorithms and content hurts everyone—many a long-lasting friendship has been formed over message boards and chatrooms—it's particularly harmful to kids. Kids need a space to be themselves with other kids.

Websites geared specifically towards kids, with extensive moderation and chat filters, allowed kids to build a sense of online community. Sites like Poptropica and Wizard101 also encouraged user creativity and self-expression. For kids whose first language was not English, these communities gave them a mutual language to communicate with others—the language of games.

While many of these sites did come with paid tiers—and, in the case of Webkinz, you had to buy a plushie to create an account—they were not freemium the way many sites are today. You could enjoy hours of entertainment and community without having to pay a cent. Unfortunately, kids do not have spending money of their own, begging parents for robux and other e-currencies.

This meant that the target demographic of these websites could not be advertised to. Kids' sites were not financially lucrative. Once their target demographics aged, many of these sites shut down or greatly reduced capacity.

Think Of The Children

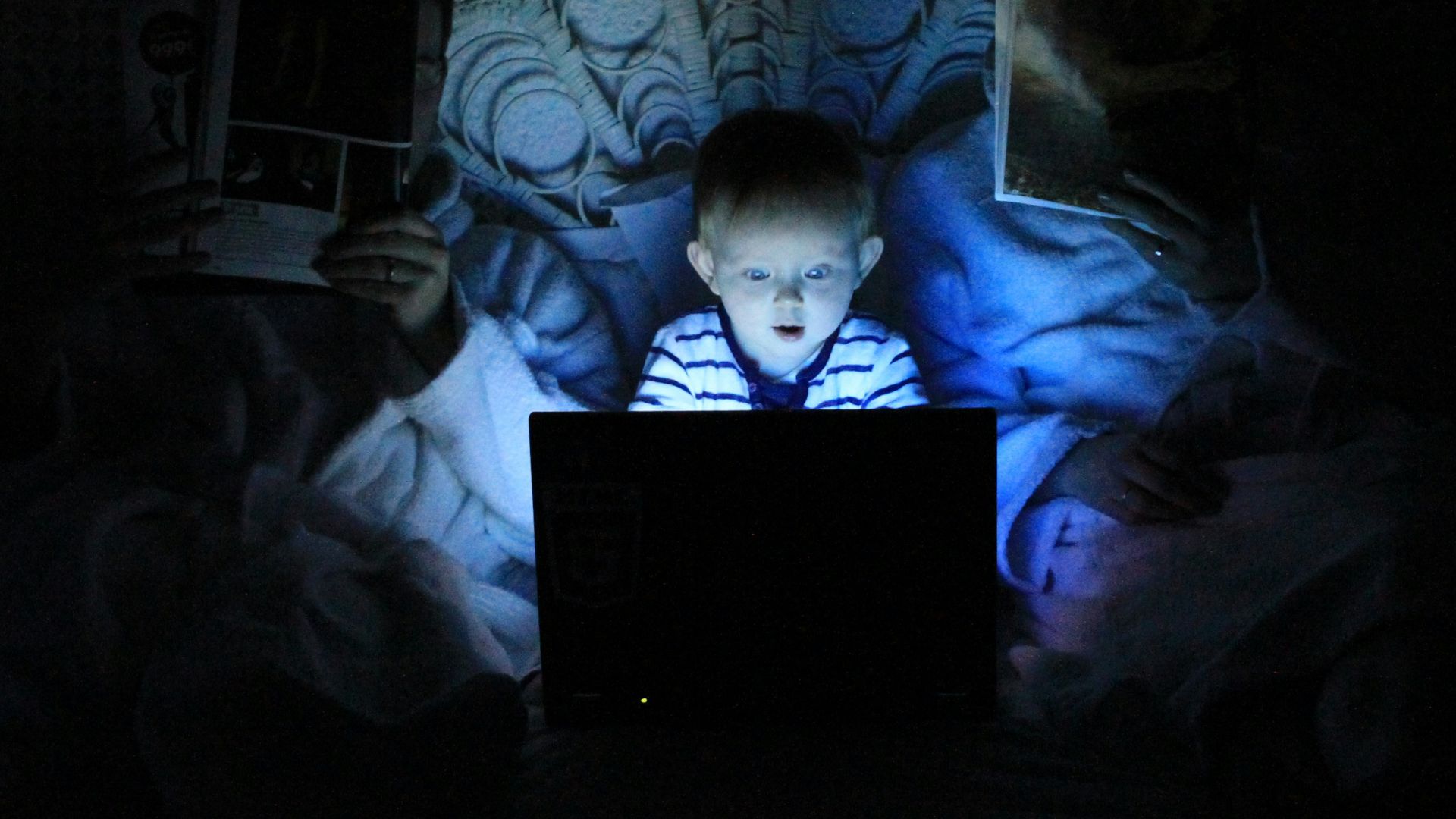

With no dedicated spaces for them, kids have been pushed into adult and young adult-oriented spaces, particularly social media. TikTok is the most famous example, but Snapchat, Instagram and Twitter have their fair shares of users under 13. There are a multitude of problems with this.

First, there is the obvious danger that kids will be easier to prey upon if there is no online separation between them and adults. Kids' sites often taught Internet safety; without it, young Internet users do not know how to defend themselves and are more vulnerable than ever. Kids being in adult spaces can lead to grooming and manipulation tactics.

Next, there is the problem of advertising. TikTok and YouTube have picked up on the fact that, while kids may not have disposable income beyond allowance money, their parents certainly do. This leads into a culture of Gen Alpha influencers and Sephora kids.

Influencers can enable poor behavior—overconsumption and body-checking are just two examples—in followers of all ages, but, as we said, kids are particularly susceptible. Not only does being fed non-stop influencer content make kids grow up too fast, but it can also make them screen-addicted and materialistic. Kids today don't have online friends so much as they have parasocial role models.

Even communities that are ostensibly for children such as Minecraft and Roblux are not without their problems. They can encourage unhealthy spending in those who have not been taught financial sense. They can also be breeding grounds for toxicity, with unmoderated chats facilitating cyberbullying.

Lastly, there is one other issue about the decline of kids' spaces that must be addressed. Getting rid of these spaces don't just hurt kids—they hurt everyone. Children are people too, but adults need their space.

If children are going to be allowed unmonitored access to every corner of the Internet, then every corner of the Internet must be sanitized for their safety. Language and discussions around marginalized groups are censored by users and discouraged by algorithms, never mind that children may also be part of these marginalized groups. Everyone wants to "think of the children" but nobody actually does.