Wiryan Tirtarahardja on Unsplash

Wiryan Tirtarahardja on Unsplash

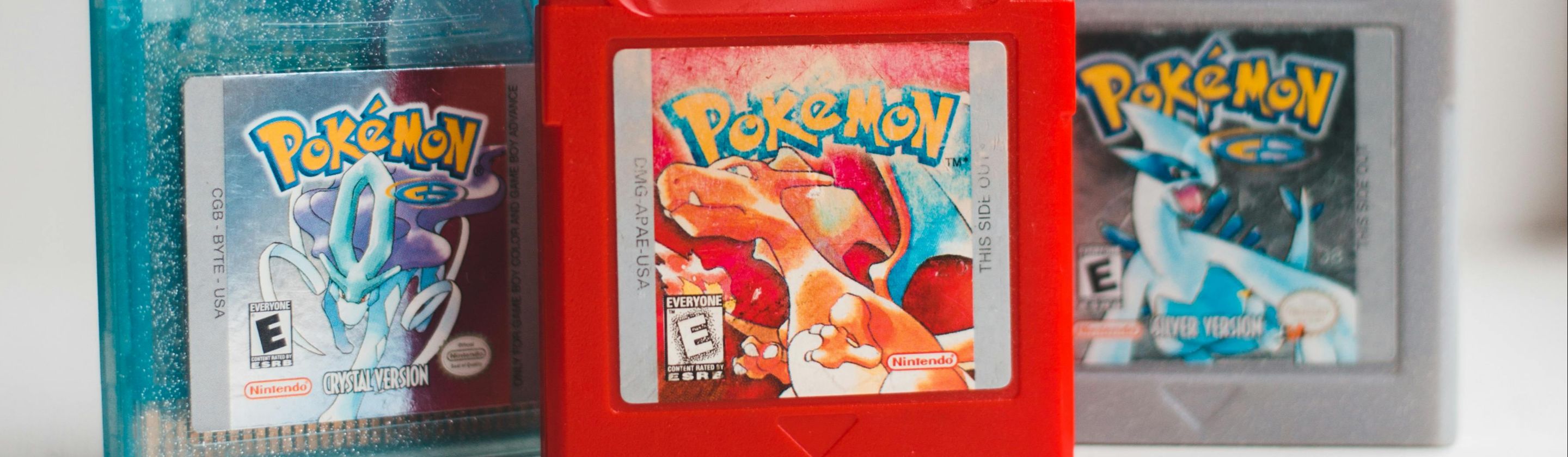

The gray Game Boy cartridge clicked into place with a satisfying snap. The screen flickered to life with chiptune music and pixelated creatures that would define childhood for millions. When Pokémon Red and Green launched in Japan on February 27, 1996, nobody predicted they would become the best-selling games in Japanese history or spark what Time magazine would call a multimedia barrage unlike any before it. The games sold 31.38 million copies worldwide, making them the bestselling Pokémon titles ever released, yet their influence extended far beyond sales figures.

What creator Satoshi Tajiri conceived as a digital version of his childhood insect collecting hobby transformed into something unprecedented: a game that required social interaction to complete. The mechanic seems obvious now, yet in 1996, placing friendship at the center of a gaming experience represented a radical departure from solitary play. The original Pokémon games did not just entertain a generation; they rewired how young people thought about gaming, friendship, and shared knowledge.

The Social Architecture That Changed Gaming

The Link Cable represented more than a technical accessory. The gray cord connecting two Game Boys became the physical infrastructure for an entirely new kind of play. Different versions of the game contained exclusive Pokémon, making it impossible to complete the Pokédex without trading. The box art openly stated that collecting all 151 Pokémon required linking to the other version, essentially demanding social play. Kids who wanted to become true Pokémon Masters needed to find other players, negotiate trades, and build networks of fellow trainers.

This design decision placed social interaction at the center of gaming in ways that seemed revolutionary for handheld devices. The trading aspect necessitated player-to-player interaction in an era before online gaming was commonplace, transforming gaming from a solitary to a communal activity. Children would gather during recess, after school, and at organized events to trade and battle. The Game Boy's portability meant these interactions could happen anywhere, granting players freedom to achieve social play outside traditional gaming spaces like arcades or living rooms.

The mystery of Mew amplified the social dynamics. Game Freak programmer Shigeki Morimoto added the mythical Pokémon as a prank, hiding it in unused code space. When rumors spread that a 151st Pokémon existed, Nintendo partnered with CoroCoro Comic to distribute Mew to 20 contest winners. The contest received 78,000 entries. Monthly sales that had plateaued suddenly equaled weekly sales, then tripled and quadrupled according to Tsunekazu Ishihara, who helped create the franchise. The power of word-of-mouth drove sales before internet forums and social media existed to spread information. Kids became experts on a topic that interested them, developing specialized knowledge they could leverage for social status among peers.

The Knowledge Ecology That Distributed Expertise

Pokémon created what researchers called “a highly distributed knowledge ecology.” Information and learning circulated across different players, different sites, and different media platforms. No single player could know everything about the game, creating interdependence among the community. Some players specialized in battling strategies. Others memorized type matchups and evolution levels. Still others focused on finding rare Pokémon or discovering glitches. This distribution of expertise meant that every player had something valuable to contribute.

The franchise's multimedia approach reinforced this distributed knowledge. The video game, trading card game, animated television series, movies, and merchandise all fed into each other, creating a transmedia ecosystem where expertise in one area translated to others. Attacks that proved effective in the anime could be implemented successfully in strategy in the video game. Card game mechanics introduced players to statistical thinking about damage calculations and probability. According to Anne Allison, professor of cultural anthropology at Duke University, Pokémon was game-based, making it more interactive than a mere anime or movie and impacting children's lifestyles in new interactive ways.

Cultural anthropologist Mizuko Ito noted that what differentiated contemporary social media like Pokémon was that personalization and remix became a precondition of participation. Players customized their teams from 151 different characters, with each character capable of learning different moves and evolving in specific ways. The number of possible team combinations was staggering. Players could choose to focus on favorite types, maximize battle effectiveness, or simply collect creatures they found aesthetically appealing. The game provided strategic depth while remaining accessible to young players.

The Cultural Breakthrough That Redefined Possibility

Pokémon arrived in North America in September 1998 after a protracted localization process. The games became the fastest-selling Game Boy titles, moving 200,000 copies within two weeks and 4 million units by year's end. The franchise rapidly saturated American culture. Pokémon appeared in the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade. A dedicated store opened in New York City. The franchise graced the cover of Time magazine in 1999 and appeared in episodes of The Simpsons and South Park. Suddenly, Japanese media had achieved something previously unthinkable: mainstream American cultural dominance.

Anne Allison wrote that before the 1990s, Japan figured little in the face of worldwide hegemony of Euro-American cultural industries, particularly that of the United States. Hollywood remained hostile to imports, and foreignness was largely seen as an impediment to mass popularization. The surprise success of Pokémon represented an undeniable breakthrough in the homeland of Disney that changed preexisting assumptions about the U.S. marketplace. Sociologist Yoshinori Kamo interviewed American children and found that kids who thought Pokémon was cool were more likely to believe Japan was a cool nation.

The franchise's influence on the first post-Pokémon generation proved lasting. These kids grew up with ubiquitous social gaming and convergent media as a central part of their peer culture. The game taught them that media could mobilize them to do something rather than serving as an end in itself. The content invited collection, strategizing, and trading activity. As these children aged into teenagers, they brought experiences from Pokémon to their participation in the teen social scene, approaching online community spaces like MySpace and Facebook with expectations shaped by earlier networked play.

We might trace our current expectations about multiplayer gaming, social features, and networked play directly to those Link Cable connections on elementary school playgrounds. The games taught a generation that knowledge sharing enhanced rather than diminished individual experience. They demonstrated that expertise could be distributed across communities rather than concentrated in individuals. The gray cartridge that clicked into place nearly three decades ago shaped not just how we play games, but how we think about learning, friendship, and the possibilities of shared cultural experience. The pixels may have been crude and the music simple, yet the lessons about connection proved remarkably sophisticated.