Brookhaven National Laboratory on Wikimedia

Brookhaven National Laboratory on Wikimedia

Long before video games became something you downloaded or streamed, they existed as curiosities built by scientists who weren’t trying to entertain the world. In the late 1950s, screens were rare and the idea of “gaming” didn’t exist yet. Still, inside a quiet research lab, a glowing dot began to move back and forth across an oscilloscope screen. That motion marked the beginning of video games as we understand them.

The game was called Tennis for Two, and its simplicity is exactly what makes its story matter.

A Science Lab Accidentally Invents Fun

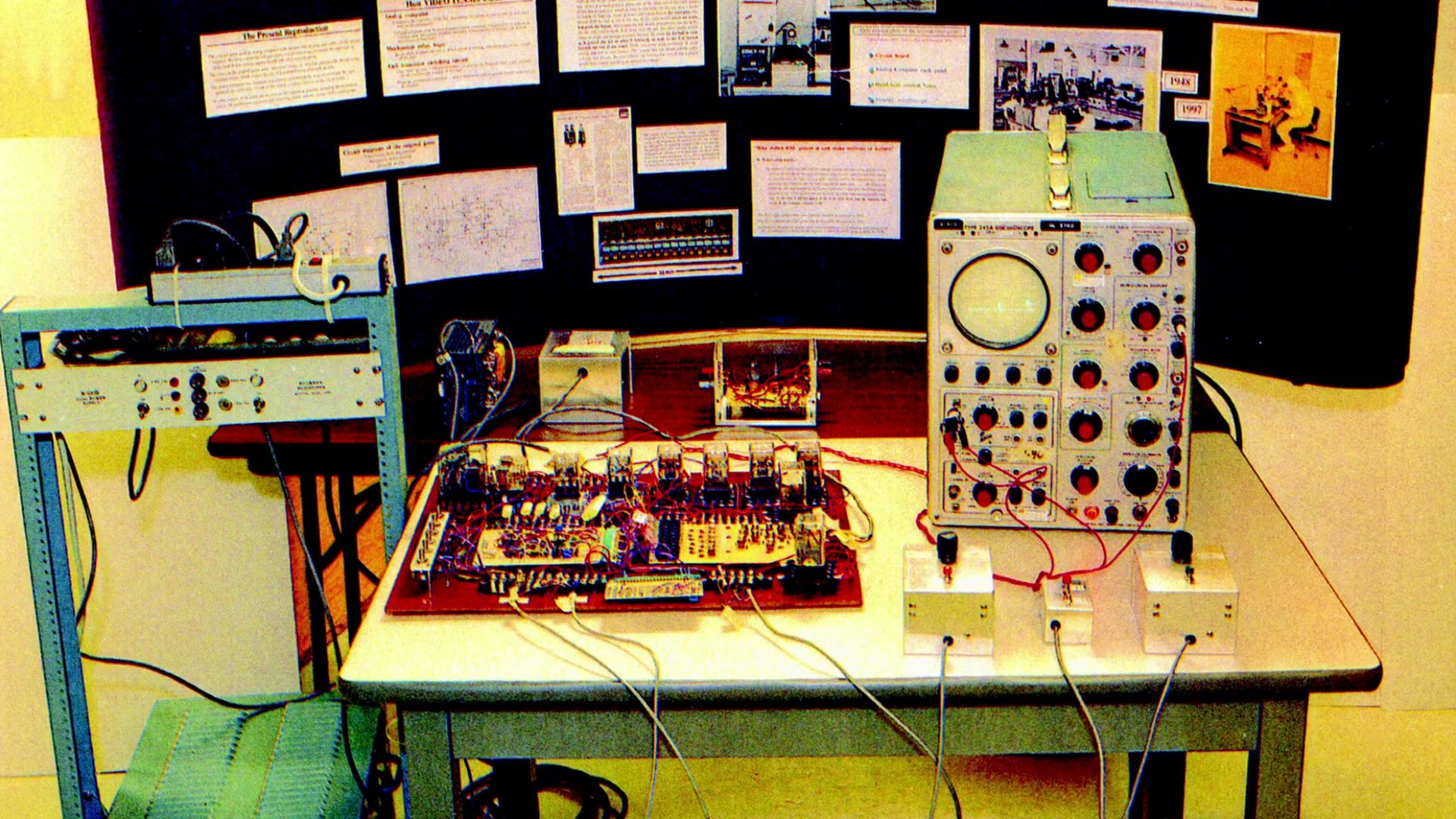

The story begins in 1958 at Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York, a government-funded research facility focused on nuclear physics. Each year, the lab hosted an open house to show the public what scientists were working on. Most exhibits involved static displays with explanations that required patience. Physicist William Higinbotham noticed that visitors often seemed bored, and he wondered if there was a better way to hold their attention.

Instead of explaining physics with charts, Higinbotham decided to demonstrate it. Using an analog computer and an oscilloscope, he designed a simple interactive simulation of a tennis game. The physics were real: gravity affected the ball’s arc, and players could adjust their shots based on timing and angle. The goal was simply to make science feel alive.

That intention shaped everything about Tennis for Two. The game displayed a horizontal line as the court, a short vertical line as the net, and a dot representing the ball. Two players held aluminum controllers with a button and a dial. Pressing the button hit the ball. Turning the dial changed the angle. That was it. No scorekeeping. No sound. No characters. Yet people lined up to play it, taking turns and laughing when they missed.

Why Tennis For Two Felt Revolutionary

Brookhaven National Laboratory on Wikimedia

Brookhaven National Laboratory on Wikimedia

Earlier computer experiments had produced images or calculations, but they weren’t designed for human play. In this case, the screen responded instantly to a player’s action.

That feedback loop is the foundation of all video games, and Tennis for Two established it almost accidentally. Players didn’t need technical knowledge to participate. They didn’t need instructions beyond “press this button.” For a moment, complex machinery became approachable.

The game’s tennis theme mattered too. Sports were already familiar, which made the experience intuitive. People understood the basics without explanation. Still, the game was never patented or commercialized. After the open house events, the setup was dismantled, and its components were reused. Higinbotham himself didn’t see it as an invention worth claiming. He viewed it as a temporary exhibit. That decision would shape how history remembered the game.

For years, Tennis for Two was barely mentioned in discussions of video game history. Later games like Spacewar! and Pong gained more recognition because they were distributed and monetized. Yet many of their core ideas echoed what had already happened in that Brookhaven lab.